Bollywood Rules, OK?

Is

film a fair reflection of the society that creates it, if

as fiction, not quite a faithful one? Or does film project an

image of its own? And what of other cultures? Does Bollywood

reflect india, or does it project India?

Is

film a fair reflection of the society that creates it, if

as fiction, not quite a faithful one? Or does film project an

image of its own? And what of other cultures? Does Bollywood

reflect india, or does it project India?

Vir Sanghvi thinks he has found the answer.....

It’s a funny thing but it happens to all of us. You know the feeling: you hear of somebody, you pick up an idea or someone tells you something — and then, suddenly, nearly everywhere you go it crops up again and again. It happens most often to me when I hear of somebody new and then discover that this person’s name turns up in conversations all the time. Or I learn a new word and then no matter what I read, that word seems to appear.

That’s how I feel about Bollywood these days.

Not that Bollywood is ever far from our thoughts: the hoardings, the stars, the gossip items and even the films themselves are an integral part of the 21st Century Indian landscape. But what’s intrigued me about the many references I have heard to Bollywood over the last month is that they have all been somewhat unusual in nature.

It started last month when I went to Paris to speak on the politicisation of the Indian middle class at an academic forum. The audience was intelligent, highbrow and well-informed. This meant that I had to pitch the lecture at a relatively advanced level and then tense myself for the probing questions that followed.

TALKING POINT

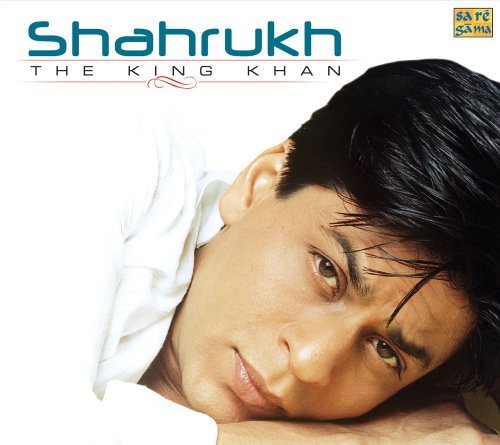

But what surprised me were the conversations at the drinks break that followed the talk. Of course, the audience had heard of India’s success as the world’s largest democracy. But the major reference points — the ones they had some tactile experience of — were not the BJP or the Congress. They were Shah Rukh Khan, Devdas and the entire Bollywood phenomenon.

A

week later, I moderated a discussion between NK Singh, Montek Singh

Ahluwalia and Chris Patten at the first Oxford-India Forum. The

discussion focused on the India-China economic race but when it was

Patten’s turn to make a speech, he introduced himself in a slightly

unusual manner. As you probably know, he has been a minister in the UK

government, the last Governor of Hong Kong, an EU Commissioner, a

best-selling author and is currently Chancellor of Oxford University.

Nevertheless, this is how he chose to introduce himself: “I am probably

best known as the father of Alice Patten who acted in Rang De Basanti.”

Ten

days later, I was at the India Today Conclave interviewing Karan Johar

on stage. Though the Conclave was intriguingly non-political this year,

it was clear — judging by all the people I spoke to afterwards — that

Karan was one of its biggest hits. His session was packed and all that

the delegates wanted to discuss was Bollywood.

And then, yesterday, I shot a television programme with Soha Ali Khan and Pramod Mahajan.

Though this is not widely known, Pramod is one of Delhi’s great film buffs: he must own over 1,500 DVDs. Inevitably, the discussion turned to Bollywood, Rang De Basanti and whether that film’s message to the young had anything to do with the spontaneous outpouring of public outrage over the Jessica Lall verdict.

“Of course, Hindi films influence society,” said Pramod. “Nobody can deny that.” Soha was more modest in the claims she made on behalf of her film but even she conceded that she had noticed the parallels. Many of the Jessica Lall protests seem straight out of the film. Not only did they take place at India Gate but some of the news channels even copied the shots that Rang De Basanti had used for its India Gate protest sequence.

Which is why I say that for the last month, there has been no getting away from Bollywood.

At one level, this is not strange because we have always been a film-crazy society. But what intrigues me about the manner in which Bollywood keeps cropping up in conversations these days is quite how seriously we now take the Hindi film industry.

BOMBAY BOY

Because I grew up in Bombay and because my father knew many film stars, I never shared the usual upper middle class contempt for the movie world. At a time when many of my colleagues regarded actors as over-made-up jokers, I was quite happy to write about them or do articles on films. (It is quite ironic that I spoke to Karan Johar at the India Today Conclave; in 1977, I wrote that magazine’s first film cover story and I remember having to persuade Aroon Purie that a national news magazine had to cover films. He only conceded the point when I pointed out that even Time magazine did it.)

But what none of us imagined in the 1970s was that Bollywood would grow to be India’s advertisement for itself. Even in the 1980s, few of my friends would have considered joining Hindi films and many refused pointblank to see any of them.

Now everybody watches Hindi movies; and, show me a pretty teenager who says she will refuse a Bollywood offer and I will show you a liar.

Each

time I interview someone like Karan Johar, I am always struck by how

much the profile of the average Hindi film director has changed. Gone

are the days of the Prakash Mehras and KC Bokadias. The new generation

of directors comprises people like Sanjay Bhansali, Aditya Chopra and

Rakeysh Mehra who could easily make successful Hollywood films and who

are as well-travelled and sophisticated as anyone I know.

Nor are they deluded about the unreality that Hindi cinema sometimes requires: at the Conclave, Karan had the audience in splits with his description of how Shah Rukh Khan managed to run across New York in no geographical order (in Kal Ho Naa Ho) despite the hole in his heart. “But what’s a Hindi film if the hero doesn’t get to run in the end,” he laughed.

But most important is how Bollywood has become the great unifier. Not only does it unite Indians in every corner of the country, its appeal cuts across all social strata. And, as Karan pointed out, it also unites Indians across continents. Many of Yash Chopra’s films can recover their investment on the basis of overseas profits alone.

Over a decade ago, I accompanied Amitabh Bachchan on a tour of Guyana, the one West Indian country that is on the South American mainland. Nobody there spoke any Hindi. And yet, the country came to a standstill because Amit was visiting.

ANCESTRAL LINKAGE

They loved him and they loved his films even though they had to see them with English subtitles. But the language didn’t matter. As far as they were concerned, Hindi films marked the one link with their ancestral roots that was still relevant to their lives.

At the India Today Conclave, many people asked Karan whether he wanted an Oscar. Others wanted to know when India would produce a Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon or some kind of crossover film which would reach mainstream Western audiences. Karan’s response was that, in his experience, when you tried too hard to cross, it was usually over.

WE DO IT OUR WAY

I tend to agree with him. One of the strengths of Hollywood is that nobody bothers how a film will play in Hong Kong or Hyderabad. They make their movies for their domestic audiences. And if the rest of the world wants to enjoy them, they are welcome to buy tickets.

SO DO WE

So it is with Bollywood. India remains the only non-American source of global popular culture. When Shah Rukh Khan travels to many Third World countries, it is as though a hurricane has struck. Even in New York, where Shah Rukh was recently shooting at Grand Central Station (for Karan’s new movie), the authorities were blasé about the security that would be required. After all, they said, Tom Cruise had just finished shooting for Mission Impossible 3 there and nobody had bothered the crew.

As it turned out, the moment people — not just Indians, but Asians and Africans of all nationalities — found out that Shah Rukh was in the building, the crowds became unmanageable and the shoot had to be aborted.

PURSUING THE YANKEE DOLLAR

It would be a mistake for Bollywood to change itself in pursuit of the Yankee dollar. To do so would be to compromise on the fundamental character of our movies and on all the things that make Indian popular culture a craze all over the world. Yes, all right, our films may not gross as much as Titanic. But they gross more than enough to keep our industry going.

And each year, our producers find more and more global success.

My concern is that we sometimes deny Bollywood the credit it deserves as an ambassador for India. Ultimately, the reason America dominates the globe today is not because somebody like George Bush has the military muscle to launch an ill-advised invasion of Iraq. It is because American popular culture — from movies to music to jeans to pizza — has come to rule the world.

Its only rival is Bollywood. And I think we should celebrate that success. And take pride in it.