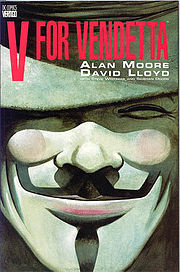

ILLUSTRATOR DAVID LLOYD - Creating anarchy in the UK

"When we originally wrote V for Vendetta it was 1980-81, and Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. She had only just started and the full weight of her influence only came about later with the miner’s strike in ’84, stuff like that, and it was around that time that we started to emphasise the political message and it became much more important to add those things as time went by. For me, the most important message is about individualism: the individual’s right to be individual and not be forced by fear into conformism. That’s the central message of it now, really."

"When we originally wrote V for Vendetta it was 1980-81, and Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. She had only just started and the full weight of her influence only came about later with the miner’s strike in ’84, stuff like that, and it was around that time that we started to emphasise the political message and it became much more important to add those things as time went by. For me, the most important message is about individualism: the individual’s right to be individual and not be forced by fear into conformism. That’s the central message of it now, really."

Can you say how the idea for the graphic novel developed?

Can you say how the idea for the graphic novel developed?

“Yeah, I was involved with a magazine called Warrior which wanted certain different types of characters and I was asked to write and draw, originally, a masked vigilante character. That was the whole brief. At the time I didn’t want to write it, and I knew Allan Moore, and I’d worked with him very well, he’s a great writer and I liked him a lot, so we got together and came up with this character, which originally went through a whole bunch of embryonic stages. One stage he was going to be a kind of policeman, then a different kind of thing. Allan wanted something that was theatrical but this character was an urban guerrilla that was fighting a government. That was the basic core that we had for it. One of the great anarchists of British history is Guy Fawkes, who was one of a bunch of conspirators who plotted to blow up the Houses of Parliament and disrupt the government in 1605. He is a classic character in British history, and it was a great idea for this character, this guy who is fighting this dictatorship, to adopt this character as his persona. Also it was a character that’s slightly crazy, so it was the ideal thing to use. So that’s how the concept came about. And then, as I say, we developed this for a monthly magazine, it continued for about 26 chapters and then the magazine folded, and then eventually DC Comics in America bought it, printed it, and we completed it in 1990. So that’s how it all came about and the graphic novel is a collection of those stories.”

Was it your idea to have it be a mix of the Phantom of the Opera and the Count of Monte Cristo or was it just in the film?

“The Count of Monte Cristo thing is something that Larry and Andy came up with.”

Did you ever think about your graphic novel becoming a film?

“Yeah, in fact in the early days when we were still doing it in its early form, we were trying to sell it as a TV show. We actually sent letters to a producer called Verity Lambert in England to try and interest her. We were sending it everywhere. And at one stage we were trying to interest an animation company in it. So it’s no surprise to us that, thankfully, at the end of the day, there’s been great movie interest in it. But yeah, we always thought about that. The thing that initiated the story to begin with was all TV and movie influences. The Prisoner was one of the great influences on it. There was another thing called The Guardians. Myself and Allan were both influenced by British TV and Hollywood movies. We had the same influences so we blended together very well and came up with this idea. Also there was a movie called The Abominable Dr Phibes, with Vincent Price, which also stimulated the ideas. Also, the Shakespearean quotes, that concept initially came from another Vincent Price movie called Theatre of Blood, in which he would quote Shakespeare. There were a lot of influences. Phantom of the Opera, all that sort of stuff. We blended it all together and made this construct that worked very well, I think.”

Frank Miller co-directed Sin City. Did you think of co-directing this?

“I should be so lucky. No, I’m just a drawing board jockey. I just sit and draw it. It’s a hard enough job doing that, you know. I don’t think I’d like to get onboard with the kind of work these guys do.”

You originally wrote V for Vendetta as a reaction to Margaret Thatcher. Would you be able to write something similar today? It seems like we’re going backwards in some respects.

“Well, in British terms, we really don’t have a Thatcher anymore, thank God. We had 17 years of Conservative government. When we originally wrote it, it was in 1980-81, and Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. She had only just started and the full weight of her influence only came about later with the miner’s strike in ’84, stuff like that, and it was around that time that we started to emphasise the political message and it became much more important to add those things as time went by. For me, the most important message is about individualism: the individual’s right to be individual and not be forced by fear into conformism. That’s the central message of it now, really.”

Fear is being used in Britain to some extent just as it is being used to a greater extent to control the populace in America. It’s like we’re going forwards to go backwards.

“Well that’s the nature of society, isn’t it? It’s like one step forward and one step back. It’s a cycle isn’t it?”

What were your thoughts after the bombings in London?

“Terrorism isn’t new to London. The IRA were putting bombs in London, and all over the country, in fact, at the time we were drawing and creating V originally. None of it’s new. And sadly I don’t think any of it will change. It’s just one of those facts of life.”

There seemed to be Sex Pistols references in the film and I wondered whether they represented a form of anarchy, or an idea of anarchy, that went away under Thatcher?

“Yeah, well, anarchy is a very attractive thing. Everybody wants to have no responsibilities and to bust up any regime that’s telling you what to do. It’s important. The message of the film is that freedom is the most important thing you can have, and I think that’s the same for any situation.”

Were the Pistols an influence, though? There are several apparent references, and the repeated use of the word “bollocks”.

“No, not for me. Alan was very influenced by music. But the general attitude of being able to bust up an establishment that is being oppressive, that’s a simple message. It’s a message of simple rebellion, really, which myself and Alan did subscribe to. Anyone that loves freedom is going to subscribe to that really, I guess.”